The Dawn of Bioprinted Organs: Tracking the First Human Recipients

Five years after the world’s first successful transplant of a 3D-printed human organ, the medical community is holding its breath. What began as a daring experiment has evolved into a quiet revolution, with the initial cohort of patients serving as unwitting pioneers in what may become medicine’s most consequential breakthrough since antibiotics.

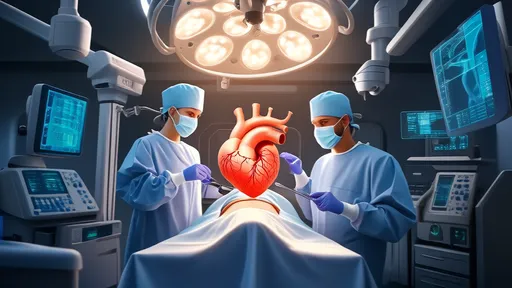

At the University of Sydney’s Advanced Biomanufacturing Centre, Dr. Eleanor Chen flips through a thick dossier of post-operative scans. "We’re not just monitoring organ function," she explains, tapping a CT image of what appears to be a perfectly ordinary kidney. "We’re watching evolution unfold in real time – human cells learning to behave as architecture." The kidney in question, printed from the patient’s own cells in 2022, now filters blood with 93% efficiency – a figure that shocked the surgical team when it surpassed the donor organ’s typical 80-85%.

The Silent Revolution

Unlike the media frenzy surrounding the initial surgeries, follow-up reporting has been sparse. This isn’t due to failure – quite the opposite. The mundane nature of success proves startling. Of the 17 living recipients tracked by the International Organ Printing Consortium, none have experienced acute rejection. The printed livers have regenerated damaged sections with what researchers describe as "embryonic vigor," while the trachea implants have developed vascular networks that textbooks claim shouldn’t exist.

Marta Herrera, a 54-year-old grandmother in Barcelona, received a bioprinted pancreas three years ago. "People expect me to glow in the dark or something," she laughs during our video call, holding up a jar of homemade marmalade made with oranges from her garden. Her glucose levels have remained stable without immunosuppressants, a feat impossible with traditional transplants. Yet what fascinates researchers more is how her implant’s beta cells have spontaneously organized into micro-islets – a biological pattern not seen in natural pancreases.

The Ghost in the Machine

Not all findings inspire celebration. Dr. Yusuke Tanaka’s team at Kyoto University made an unsettling discovery last year: printed cardiac patches implanted in rabbits began exhibiting electrical conduction patterns resembling neonatal hearts, even in mature animals. "It’s as if the cells forget they’ve been reprogrammed," Tanaka notes. While this hasn’t caused harm, the phenomenon challenges fundamental assumptions about cellular memory.

Perhaps most perplexing are the psychological reports. Transplant psychiatrist Dr. Livia Weber has documented a curious pattern among recipients. "They describe dreams of floating through coral reefs or vine-covered ruins," she says. "The imagery consistently involves intricate biological structures." Weber speculates this may represent subconscious processing of unfamiliar somatic signals, though she admits the consistency across cultures and age groups defies easy explanation.

The Manufacturing Paradox

Production challenges remain formidable. The much-publicized "printing" process actually involves weeks of cellular scaffolding maturation in bioreactors that mimic fetal conditions. Dr. Aaron Felstein at MIT estimates current costs at $250,000 per organ – still cheaper than a lifetime of dialysis, but far from accessible. "We’re essentially rebuilding evolution’s work from scratch," he remarks, gesturing to a bioreactor humming softly in his lab. "Nature had billions of years to perfect this. We’re trying to do it before our funding cycles end."

Ethical debates simmer beneath the technical triumphs. The Vatican’s Pontifical Academy of Sciences recently convened an emergency panel to discuss whether bioprinted organs containing neural crest cells (used in some adrenal gland constructs) could theoretically develop consciousness. Meanwhile, black market rumors persist – a Shanghai hospital reportedly turned away a businessman offering $2 million for an unauthorized liver printing last year.

Looking Forward

As second-generation bioprinted organs enter clinical trials featuring enhanced vascular networks and built-in biosensors, the initial recipients continue their quiet lives. Their bodies harbor the most sophisticated biological machines ever human-made, yet their daily concerns remain wonderfully ordinary: gardening, grandchildren, the occasional doctor’s appointment.

Dr. Chen summarizes the situation while reviewing a patient’s latest lab results: "We set out to replicate nature, but nature had other plans. These organs aren’t just surviving – they’re becoming something new." The computer screen before her displays pulsing clusters of cells, alive with possibilities no one yet understands.

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025