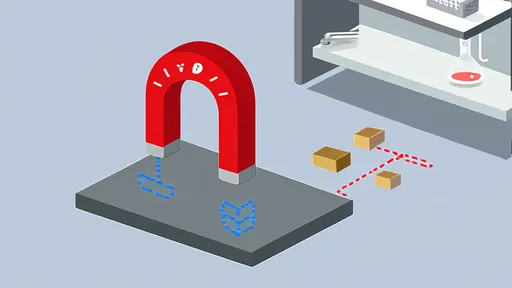

The humble refrigerator magnet is a staple in households around the world, clinging steadfastly to metal surfaces while utterly ignoring others. Yet, have you ever wondered why these colorful little objects seem to have a preference for iron or steel but show no interest in copper or aluminum? The answer lies in the fascinating interplay between magnetism and the atomic structure of materials.

At its core, magnetism is a force that arises from the movement of electric charges. In certain materials, such as iron, nickel, and cobalt, the electrons within the atoms align in a way that creates a magnetic field. These materials are known as ferromagnetic, meaning they can be permanently magnetized or strongly attracted to magnets. When you place a refrigerator magnet against an iron surface, the magnetic field induces a temporary alignment of the electrons in the iron, creating an attractive force strong enough to hold the magnet in place.

Copper, on the other hand, behaves quite differently. It is classified as a diamagnetic material, which means it generates a weak magnetic field in opposition to an externally applied magnetic field. This repulsion is so minuscule that it’s barely noticeable in everyday life. While a refrigerator magnet does interact with copper, the effect is far too weak to produce any visible attraction. In fact, if you were to drop a strong magnet down a copper tube, you might observe a slight slowing of the magnet’s fall due to this diamagnetic repulsion—a phenomenon often demonstrated in physics classrooms.

The distinction between ferromagnetic and diamagnetic materials boils down to their electron configurations. In ferromagnetic materials, unpaired electrons in the atoms’ outer shells align their spins in the same direction, creating a net magnetic moment. This alignment can persist over large groups of atoms, forming what are known as magnetic domains. When exposed to an external magnetic field, these domains align, reinforcing the field and resulting in strong attraction.

In contrast, diamagnetic materials like copper have all their electrons paired, leaving no unpaired spins to create a net magnetic moment. When a magnetic field is applied, the electrons in these materials adjust their motion slightly to oppose the field, generating a weak repulsive force. This fundamental difference in electron behavior explains why your fridge magnet sticks to the steel door but slides right off a copper pot.

Beyond the basic science, the choice of materials in everyday objects like refrigerator magnets is also a matter of practicality. Iron and steel are not only magnetic but also abundant and inexpensive, making them ideal for use in appliances and construction. Copper, while highly conductive and useful in electrical wiring, doesn’t offer the same magnetic utility. Moreover, the strength of the magnetic force required to hold up a photo or a shopping list is easily achieved with ferromagnetic materials but would be impossible with diamagnetic ones.

Interestingly, there are other classes of magnetic materials that exhibit different behaviors. Paramagnetic substances, for instance, are weakly attracted to magnetic fields but don’t retain magnetization once the field is removed. Aluminum falls into this category, which is why it, too, fails to hold a fridge magnet in place. However, the attraction is still too feeble to be of any practical use in this context.

The next time you pin a reminder to your fridge, take a moment to appreciate the invisible forces at work. That simple magnet is a testament to the intricate dance of electrons within metals, a dance that dictates what sticks and what doesn’t. While copper may not play along, its role in other technologies—like conducting electricity with minimal resistance—proves that every material has its place in the grand scheme of physics and engineering.

So, the next time someone asks why fridge magnets don’t stick to copper, you can confidently explain that it’s not a matter of preference but one of physics. The electrons in copper simply don’t cooperate in the way those in iron do, leaving your magnets to cling to more accommodating surfaces. And that’s the science behind the stick—or lack thereof.

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025