The global race to harness nuclear fusion power has entered a critical phase, with China's Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak (EAST) making groundbreaking strides that could potentially rewrite humanity's energy future. Dubbed the "artificial sun," this cutting-edge fusion reactor in Hefei has recently achieved several world-record milestones that bring commercial fusion power tantalizingly closer to reality.

China's EAST reactor, operated by the Institute of Plasma Physics under the Chinese Academy of Sciences, has become the focal point of international attention after sustaining plasma temperatures of 120 million degrees Celsius for 101 seconds in 2021 - a duration nearly five times longer than its previous record. Even more remarkably, the device briefly achieved a staggering 160 million degrees Celsius, demonstrating unprecedented control over the extreme conditions needed for fusion.

These achievements represent more than just technical benchmarks. They provide crucial validation for the tokamak design that will be used in the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) project in France, where China plays a leading role among 35 participating nations. The EAST serves as an important testbed for technologies that could eventually power the world's first commercial fusion plants.

What makes China's progress particularly significant is how rapidly the country has advanced in this notoriously difficult field. When EAST first became operational in 2006, it could only maintain fusion conditions for a few seconds. The leap to maintaining 100-million-degree plasma for minutes rather than seconds marks a fundamental shift in what's considered technically possible with current materials and magnetic confinement technology.

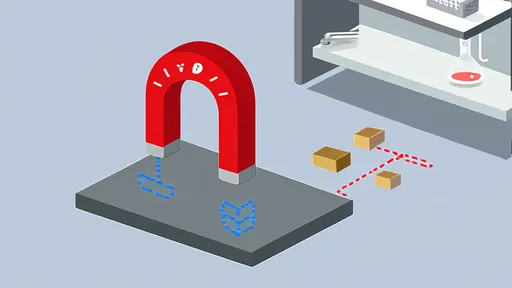

The engineering challenges involved in these experiments cannot be overstated. Containing plasma hotter than the core of the sun requires incredibly precise magnetic fields generated by superconducting coils cooled to near absolute zero. The reactor's inner walls must withstand not only extreme heat but also intense neutron bombardment - a byproduct of the fusion process that gradually degrades materials.

Chinese scientists have made several key breakthroughs to overcome these obstacles. Their development of advanced tungsten divertors - components that remove heat and impurities from the plasma - has proven particularly valuable. The EAST team has also pioneered new plasma shaping and control techniques that maintain stability at previously unattainable durations.

Looking ahead, researchers are working toward the next major milestone: sustaining fusion conditions for 1,000 seconds (nearly 17 minutes) at operational temperatures. Achieving this would demonstrate that continuous fusion power generation is physically possible with current technology, though significant engineering hurdles remain before such systems could operate commercially.

The implications of successful fusion power cannot be overstated. Unlike fission reactors, fusion produces no long-lived radioactive waste. The primary fuel - isotopes of hydrogen extracted from water and lithium - is virtually inexhaustible. A single gram of fusion fuel can theoretically produce as much energy as eight tons of oil, without carbon emissions.

China's fusion program operates as part of a broader national energy strategy that includes massive investments in renewables, next-generation fission reactors, and now fusion research. The country has committed to building a Fusion Engineering Test Reactor (CFETR) by 2030, intended to bridge the gap between experimental devices like EAST and commercial power plants.

International collaboration remains a cornerstone of fusion research despite geopolitical tensions. Chinese researchers regularly share findings with ITER partners, and many consider the EAST project complementary to other major fusion experiments like Europe's JET or America's SPARC reactor. This spirit of cooperation stems from recognition that fusion energy would benefit all humanity if successfully developed.

Still, significant challenges persist before fusion can contribute to power grids. The energy return ratio - the amount of power generated versus input - must improve dramatically. While recent experiments have come closer to break-even, no fusion device has yet produced more energy than it consumes when accounting for all system inputs.

Materials science presents another major hurdle. The neutron flux from sustained fusion reactions would quickly degrade conventional materials, requiring the development of new alloys or composites that can survive decades in a commercial reactor environment. China's materials research laboratories are working on several promising solutions, including nano-structured metals and liquid lithium shielding.

Economic factors also loom large. Even optimistic projections suggest fusion power won't become cost-competitive with renewables until at least 2050. However, as Song Yuntao, deputy director of the EAST project, notes: "We're not developing fusion as a replacement for solar or wind, but as a baseload complement that can provide continuous clean energy regardless of weather conditions or time of day."

The psychological impact of China's fusion progress shouldn't be underestimated either. Each broken record generates excitement in the scientific community and helps maintain funding for what remains a high-risk, high-reward endeavor. After decades of fusion always being "30 years away," many researchers now believe commercial viability could be achieved within our lifetimes.

As the EAST team prepares for their next round of experiments, the world watches closely. Their success or failure could determine whether fusion remains confined to laboratories or finally emerges as the holy grail of clean energy production. One thing is certain: China has firmly established itself as a leader in what may become the most important technological achievement of the 21st century.

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025

By /Jun 7, 2025